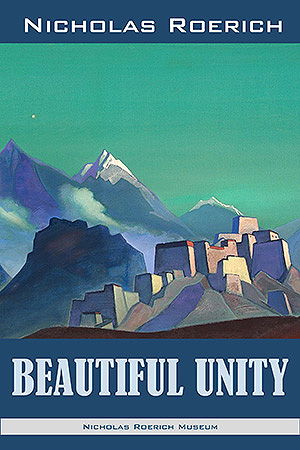

Beautiful Unity

by Nicholas Roerich

New York: Nicholas Roerich Museum, 2019.

$6 (ebook) $10 (paperback) $15 (hardcover)

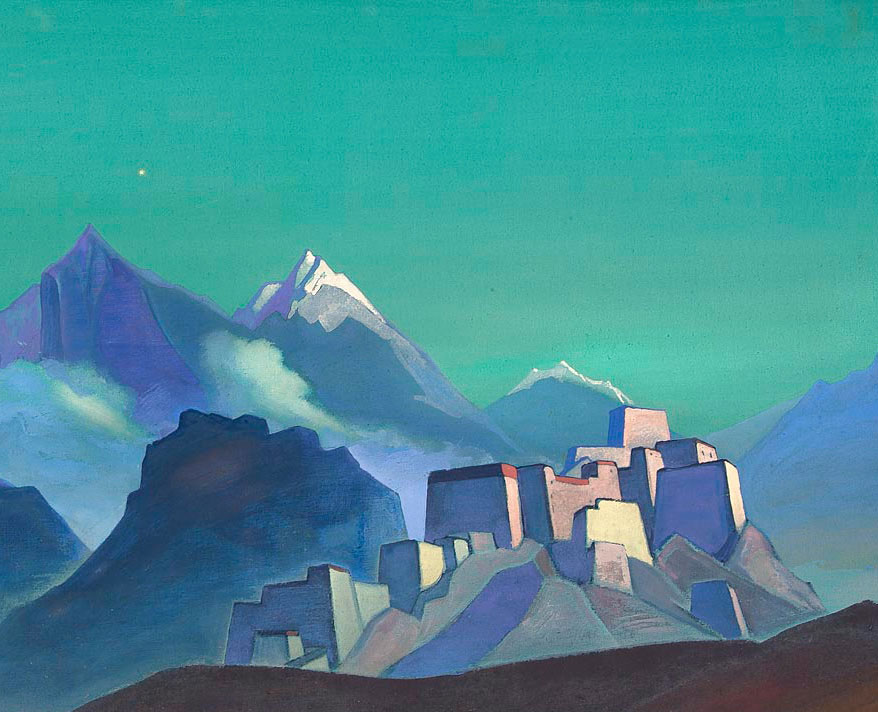

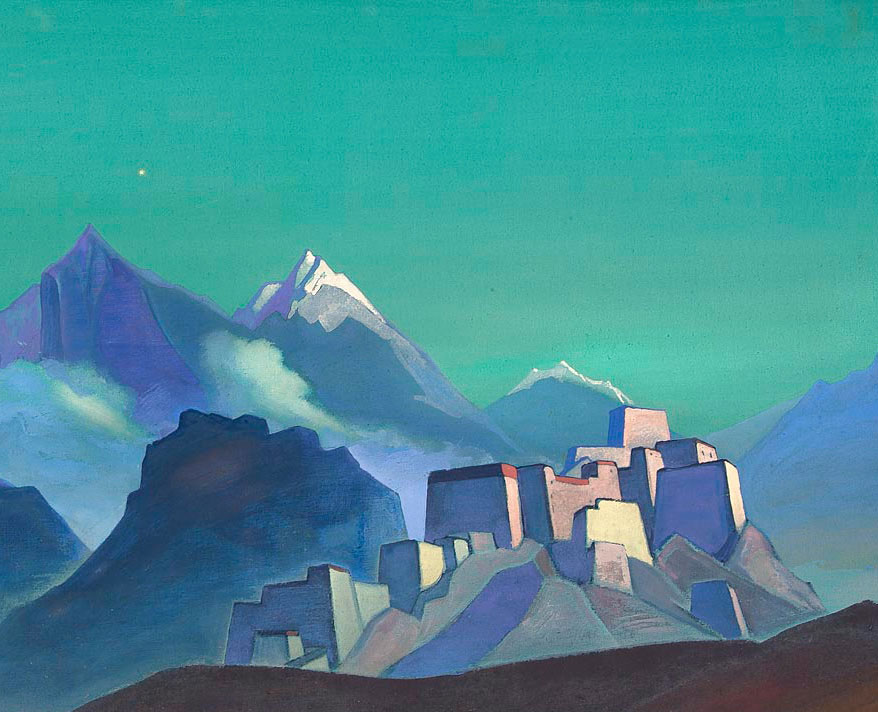

Cover illustration:

Nicholas Roerich. Star of the Morning. 1932.

Nicholas Roerich has a place all his own in the world of Art. His pen too has carved out a niche for itself in the world of letters. The brush has a wider appeal no doubt, but the pen has a distinct function of its own; and in the hands of Nicholas Roerich it has for long exerted an influence which is at once elevating and instructive. A call to Beauty implies in its essentials an appreciation of the Vision which the Artist would fain share with the world at large. That the Artist’s vision even when expressed in rhetoric can be quite as sincere as when it finds expression through line and color and form is amply evidenced by what is set forth in this volume of essays. I am happy to find that in the following pages my friend Nicholas Roerich has voiced what fundamentally every sensitive mind feels about the values of Art including what is perhaps the greatest of all Arts—the Art of Living. In this he has indeed spoken for all Artists. I am sure the book will receive the recognition which is its due.

Abanindranath Tagore

Santiniketan, March 15, 1946

Art will unify all humanity. Art is one—indivisible. Art has its many branches, yet all are one. Art is the manifestation of the coming synthesis; art is for all. Everyone will enjoy true art. The gates of the ‘sacred source’ must be wide open for everybody, and the light of art will influence numerous hearts with a new love. At first this feeling will be unconscious, but after all it will purify human consciousness, and how many young hearts are searching for something real and beautiful! So give it to them. Bring art to the people—where it belongs. We should have not only museums, theaters, universities, public libraries, railway stations and hospitals, but even prisons decorated and beautified. Then we shall have no more prisons.

Humanity is facing the coming events of cosmic greatness. Humanity already realizes that all occurrences are not accidental. The time for the construction of future culture is at hand. Before our eyes the reassessment of values is being witnessed. Amidst ruins of valueless banknotes, mankind has found the real value of the world’s significance. The values of great art and knowledge are victoriously traversing all storms of earthly commotions. Even the ‘earthly’ people already understand the vital importance of a beauty that is alive. And when we proclaim: labor, beauty and action, we know verily that we pronounce the formula of the international language. And this formula, which now belongs to the museum and stage must enter into everyday life. The sign of beauty and action will open all gates. Beneath the sign of beauty we walk joyfully. With beauty and labor we conquer. In beauty we are united. And now we affirm these words—not on the snowy heights, but amidst the turmoil of the city. And realizing the path of true reality, we greet the future with a happy smile.

Nicholas Roerich

Color, sound and fragrance are cornerstones of great synthesis. From time immemorial people have felt the great inner meaning of these expressions of the human soul. Quite recently people have begun again to remember how close are color and sound and that the three are the basic remedies against human diseases. Thus he who thinks about the conception of color does not at all associate it with paint as such, but he has in mind one of the greatest concepts of our existence.

The color value of a painting, indeed, does not mean the mere value of paint but of its harmonic correlation, as the French say “Valeur.” What does such a correlation mean? Again we must say that for him who is ignorant of the concepts of synthesis and symphony, such correlation will be an empty word.

Let us not dwell here on the deep significance of art for human life—this axiom should be clear to everyone. But nowadays we must especially stress the meaning of synthesis and the symphony of life. Synthesis will be understood by everyone to whom the concept of Culture is close. If human thinking were to remain but on the level of elementary civilization, then it would be too early to mention sacred synthesis, but where the human spirit has traveled towards Culture—that is to say, the Cult of Light—there one may already find co-operation and understanding based on synthesis.

If civilization has not saved humanity from disunity and mutual hatred, then Culture has opened the beneficial gates of synthesis, behind which we can find true co-operation.

The artists do not rest on primitive considerations of paint, but the very understanding of the sonority of color leads them to such beautiful gardens from where superb vistas of the glorious future may be seen. When we speak of synthesis and of the symphony of life, we shall not avoid powerful and enthusiastic expressions. All these domains of synthesis and symphony are uplifting and lead to the summits. Often the human eye can hardly stand the radiance of snowy peaks and it is not for the human eye to judge the splendor of these summits. But we have not been called into this world to criticize, but to labor, to admire and to follow these leading summits in continuous creation.

Create, Create and Create! Create in daytime, create at night; for creation in thought is as essential as our physical expression. In this creativeness you shall overcome the most hideous habits of vulgarity, triviality and quarrelling. People sometimes think that creators are very selfish and conceited. But these ugly properties belong to the domain of darkness. When a person “climbs” to the Light, then such an abhorrent husk drops off by itself and man becomes enlightened. His “I,” is changed into the concept of “We.”

On the same path towards the summits, man will understand the true meaning of Guruship. From the depth of darkness one can hear disgusting cries at present: “Down with culture,” “Down with heroes,” “Down with teachers.” It is a shame on humanity, but one witnesses such outcries of crass ignorance even nowadays. But he who thinks of such a refined conception as color and sound, culture and harmony, he will understand the infinite Hierarchy of Beauty and Knowledge, and having ascended the majestic stairs of achievement, he will also lead the pilgrims of life who are following behind.

It is splendid that you are young—some in age, and some in spirit. Around creativeness there must be this perpetual feeling of youth which gives incessant striving towards heroism. Countries measure their glory not by captains of industry, but by artists and scientists. Such a requirement of history places upon us the duty of incessant perfectionment. He who never ceases to ascend never becomes old.

I send you my heartiest greetings on this path towards the radiant summits and I trust that you, forgetting all petty divisions and small human moods, will progress in continuous creation, cherishing the glorious traditions of your great Motherland, India!

Nalini Kanta Gupta writes in the Triveni, in his article on the “Beautiful in the Upanishads”:

“Art at its highest tends to become also the simplest and the most unconventional; and it is then the highest art, precisely because it does not aim at being artistic. The aesthetic motive is totally absent in the Upanishads: the sense of beauty is there, but it is attendant upon and involved in a deeper strand of consciousness.”

Verily Art at its highest does not tolerate any conventionality, nor violence. In the very foundations of Be-ness lives the concept of Beauty in all its power.

We, as builders, do not deny, nor reject.

“In Beauty we are united!

Through Beauty we pray!

With Beauty we conquer!”

In India a glorious Renaissance of Art is approaching. New Schools will be opened. Exhibition Halls will be built. Museums will grow. Besides State Museums, many private collections will be founded, not only of ancient art, but of modern art as well. It would be instructive to have the annals of the names of the new private collectors. In the history of Indian Art, the names of these ardent lovers of Beauty will be given a place of great honor.

The illustrious patron of art, the Duke Moro once told Leonardo da Vinci: “He who shall venerate the name of Leonardo shall also remember Moro.”

From ancient times collecting has been a sign of stability and introspection. It is very instructive to survey the various means and ways of collecting and of studying art from our days down to the heart of antiquity. Again, as in all the spirals of growth, we see almost complete circles; yet at times, an almost elusive heightening of consciousness forms another step which is reflected in many pages of the history of art. We see how specialization and synthesis alternate. Collecting formed by the inner consciousness of the collector and united by one general idea is replaced by a classification, almost pharmaceutical, sometimes completely destroying the fire of new discoveries with its pedantry. Not so long ago, the combining of Gothic primitives with modern aspirations would have been considered a proof of dilettantism. It would have been regarded as completely taboo to simply have a collection of beautiful medals and coins. Pedantry was wont to confine its scope of vision to a certain epoch, limiting it to the objects of a certain type and character. Thus icons and primitives glowing with color were turned into iconography in which the descriptive part obliterated the true and artistic meaning.

Thus, not very long ago, the history of art was taught as a collection of anecdotes of painters’ lives, while the exposition of sculptures and the technique of painting were reduced to a summary of proportions and to the mechanics of construction, diverting and distracting attention from the essence of creative work. Peculiar textbooks began to appear in which one would come across such chapters, for example, as: “How to paint a donkey, in connection with which gray paint—which does not exist—was recommended. I remember that my attention was caught, while on a boat, by the typical argument between a mother and her little girl in which the mother earnestly asserted that the mountain in the distance was black, while the child affirmed candidly that it was blue. It seems to me that the mother’s eyes must have been dimmed by some textbook she was studying about the way to paint donkeys.”

What a joy it is for children, when from their tenderest age they see objects of true art and serious books in their homes! Of course, it is necessary that these artistic objects continue to “live” and do not find themselves in the pitiful situation of remaining upside down, sometimes for an entire decade, which means that the soul of the collector has long departed for the cemetery and that his heirs have for some reason become morally blind.

During the most recent years, we have had occasion to rejoice many times over the synthetic system of collecting which has again come into existence. Not afraid of being called eccentrics or dilettantes, the sensitive collectors have begun to group their treasuries of various objects according to an inner meaning. Thus, the most modern pictures could be combined with those masters who, in their time, burned with the unquenchable fire of bringing new methods to their creative work.

In the newest collections one sees such giant pathfinders as El Greco, Giorgione, Peter Breugel and all the noble galaxy of those who were not afraid to be considered the seekers and innovators of their epochs.

And how convincing among modern paintings are the forms of Roman art and the collaborators Giotto and Cimabue, and the icons of Novgorod and ancient Chinese artists.

As all conventionalities of division and demarcation vanish, the combined creative and spiritual findings shine before you like beacon lights outside the conventional boundaries of the nations. If circumstances do not permit bringing originals into homes, then sketches and even well-reproduced copies could permit one to entertain happy dreams about the future.

I have had occasion to write the stirring story of those collectors who began their activities when still at school. Probably many painters have had experiences like mine of having little boys, who, coming to one of my exhibitions, would bashfully hand me a dollar asking to be given a sketch in return.

Another still more moving case was when public school pupils raised a collection in order to purchase a painting. That meant that ardor was stirring and taking shape within them, and that they wanted to transmute meaningless words into facts, into conscious action. Without such an imperative impulse to action, how many light-winged, thought-butterflies singe themselves in their flutterings!

In various countries, we can help with experience and advice concerning the question of how to begin collecting. One of our immediate obligations is to open the door to those who knock timidly. And not only to open the door, but also to explain that they should knock with a firm hand without entertaining the prejudices that the use of art is a privilege available only to the rich. No, first of all it is the privilege of bright and courageous spirits who long to beautify their existence and who have decided—instead of choosing the deadly hazards of gambling—to strengthen themselves by the manifestations of the spirit of man which, like an infinite dynamo, breathes life into everything made by it. Great joys are to be found at this feast of creative impulses. And many dark places in life can be so easily brightened by the brilliant rays of admiration. It is our sacred duty to help in this.

We are speaking about collecting. Someone smiles wryly: Is it timely? Is it timely to speak of artistic values when even the richest countries are horror-stricken by the general crisis? Let us answer him firmly and with the realization of the import of our words—Yes, it is timely.

According to the latest reports, in spite of the tremendous business depression in America, the prices for art objects have not suffered any depreciation and this does not surprise us in the least; on the contrary, we consider this to be a characteristic sign of the existence of the crisis.

We have seen that during the most acute crisis in Russia, Austria and Germany, the prices of art objects did not fluctuate noticeably. In some cases the art objects were instrumental in bringing an entire state out of financial difficulties. We preserve this irrefutable fact as a proof of the true value of the spirit of man. When all our conditional values are shaken, the consciousness of man instinctively turns to that which, amidst the ephemeral, proves to be relatively the most valuable.

And the spiritual, creative values which have been neglected during the triumph of the stomach again become a shelter of refuge. Therefore it is always timely to speak of the growth of spiritual creative power and to lay stress upon collecting and preserving. This is especially needed when evolution passes through difficult moments when the solution of the current accumulated problems is not known. To solve them, however, is possible only in spirit and in beauty.

In my address on the significance of art, I gave formulae which have become the motto of the International Art Centre. I said: “Humanity is facing events of cosmic greatness. Humanity already realizes that all occurrences are not accidental. The time for the construction of a future culture is at hand. The reassessment of values has taken place before our very eyes. Amidst heaps of what is valueless, current humanity has found a treasure of world significance. The values of great art march victoriously through the storms of earthly commotions. Even the ‘earthly’ people have understood the vital importance of beauty.”

And I closed the address with the following: “Not on snowy heights, but in the turmoil of the city we pronounce these words. And realizing the path of true reality we greet the future with a happy smile.’’

These words were based on forty years’ experience. Ten more years have elapsed since then. Have the formulae then expressed changed during the period? No, the experience of many countries has confirmed and even strengthened them. We must base our conclusions on experience, and on nothing else. Theory for us is only the consequence of practice, and that same practice brings forth the happy smile with which we greet the future. May the smile of knowledge and courage become the banner of our meetings. We unite to apply knowledge; may each crumb of knowledge add spirit to our smile.

How are we to bring art into everyday life? Where are these blessed paths? Perhaps they are inaccessibly difficult? Or they may require enormous wealth? Or perhaps only spiritual giants might venture along these paths of beauty?

All assurances will be unconvincing. These doubts can be answered only by a page out of real life.

I shall take the portraits of four of my friends. They have all left us now. Only one of them was wealthy, the other three were rich only in the brightness of their spirits.

The rich collector was the Moscow merchant Tretiakov. There was nothing in his family to dispose him towards art. Rather, that old merchant family looked with suspicion on the art it did not understand. But unexpectedly young Tretiakov was drawn into a new path, and with uncertainty, guided by personal feeling, he began to collect pictures of the Russian school. He went his way alone, only now and again listening to the advice of some artist friend. And it was not by chance that the now famous Tretiakov Gallery in Moscow began to come into being. With the true intuition of a lover of paintings, Tretiakov understood that the Government generally filled its museums mainly with official productions, passing over the best work of the artists. This official physiognomy of the museums could not reflect the evolution of the national school. So has it been ever since; so far I fear it will be in the future.

Art has always blossomed with an ardent personal urge which will comprehend, find, preserve and give to the whole nation. And thus the merchant Tretiakov grasped the national task of art. He found fresh artistic talents and lightened their path. He preserved their work, surrounding them with pure delight. But he made his joy a national joy, and while still alive, gave his entire remarkable collection to the city of Moscow. The task which he had set for himself was no small one. He had not simply gathered together a mass of valuable pictures, but he made his collection reflect the whole of the Russian school. Everything that was new, brilliant, important came under the eye of Tretiakov. This taciturn, gray-haired man, in his large fur coat, indefatigably visited all exhibitions. Nothing could stop him when he considered a picture important. He would mount the steep stairs leading to the studio of the young beginner in art. He was first to see a picture finished. He was first at the opening of the exhibition. But he was also first to possess the best and most characteristic works.

It came to pass that the prizes given by the highest art institutions were considered as insignificant compared with the purchase of a picture by Tretiakov. The destiny of the beginner in art was decided not by the Academy, but by this sincere and taciturn man. When there was no more room on the walls in his house, Tretiakov built another beside it. If this was needed it had to be done. Art was not to suffer any loss.

Of course it may be said that, given Tretiakov’s great wealth, it was possible to collect on this vast scale. He was able to choose the best and could gather enough to represent the whole of the Russian school in his collection. It was true that his wealth made this scale possible, but the quality of the collection, his love of the work, and his living creative work in the choice itself of pictures and of men—all this proceeded not from the amount of his wealth, but from the untold riches of his spirit. Thus did one man, strong in spirit, do an infinitely important national work. Now, should the Government seek to establish a new Tretiakov Gallery, it would find itself powerless to do so, for it was the urge of the spirit that created that inimitable combination of beauty.

This is an instance of ideal creativeness within national limits.

Now for another spiritual portrait. Here we have the same power of a spiritual urge along with a mighty struggle with means. It was Count Golenishtchev-Koutouzov, a well-known poet and worker in the sphere of culture, and the Chamberlain at the Imperial Court. In his case, family traditions led him to develop a love of art. His historical knowledge was great, and he also had special, deep poetic gifts.

His collection consisted of pictures of the old Dutch, Flemish and Italian schools. Its fundamental characteristic was not the search for the conventional names but the truth shown in wonderful creations. The collector understood that the names of Rembrandt, Rubens, Van Dyke were purely collective names that only the lowest type of collector sought in the dark for that which was but an empty sound to him. But a better knowledge of art shows us a countless number of artists who were engulfed in the so-called great names. The task of the cultured collector is to distinguish among these forgotten names for truth’s sake. If within an excellent picture attributed to Rembrandt we find the signature of Karl Fabricius, his pupil, is this fine picture any the worse for that? Or again could Van Dyke paint two thousand portraits in one year? Of course not, but he had up to two hundred pupils.

I know how grieved the Count would be to learn that one of his favorite pictures by an unknown Flemish painter Haselaer, now hangs in the Metropolitan Museum in New York under the name of Joachim Patinir.

In the name of truth, Count Golenishtchev-Koutouzov sought to discover the real names of painters and remedied, as far as he could, the sins of mercenary human history. And what loving intimacy breathed out from his choice collection. Every new member of the collection was greeted with the disapproval of numerous relatives who begrudged the money spent on it. Money was so scarce since his small Court salary was not enough to live on. This collector departed this world surrounded by his real friends, his pictures, and he willed that his collection be dispersed to give new joy to new seeking souls.

Golenishtchev-Koutouzov was the type of refined collector who, working and rejoicing in new beauty and truth, then sends it forth again to serve for the ennobling of the human spirit.

Now for the type of a young collector—an instinctive collector who, from his school days develops a love for works of art instead of choosing the joys natural to his age. From childhood, without possessing any personal artistic capabilities, he is distinguished by education and refined taste. He is attracted to all that is beautiful. His spirit seeks to rise.

What pleasure it was to pass the time with young Sleptsov. While yet a pupil of the Imperial Lyceum, he began to collect pictures. His purchases were not chaotic, not accidental. He knew what he was doing. And all the money given to the boy by his mother for pleasures was spent on his noble pursuit. And if sometimes he was short of money, his enthusiasm for his general task never suffered because of this.

And this general task was a fine one. The boy developed a love for certain, very subtly selected painters, and decided to have specimens of each of them in all the periods of their work to preserve and to pass on to posterity a complete picture of the creative human life of each artist. The youth dreamed of the future; each painter was to have a separate room and the whole furnishing of the room was to correspond with the character of the art represented in it— the furniture, the embellishment of the walls and ceiling, the character of the lighting and floor covering. From this we may gather what subtlety of perception lay in that young soul, and what deep love and care surrounded each of the artists represented. In these special rooms, choice singing and music were to be heard at times, or suitable passages were to be read aloud. In a word the dream of Harmony of the Unity of Art was to be realized.

It was a joy to hear how a new work of art was selected for the collection. What subtle and truthful considerations were expressed for discovering and bringing out a new and worthy feature in the creative work of an artist. And you could see no mere fancy in this treatment of art, but a real cultural need. And this subtlety of culture influenced those surrounding him. Both thought and speech were purified by this bright ascension of the spirit.

Sleptsov dreamed of handing over his collection to the nation, without any care for his name. But he left us too early to do so. And he left us in an unusual way. He went out for a ride and did not return. He passed over unexpectedly, in the midst of Nature, listening to the harmony of the Cosmos. An enviable passage—a passage to new beautiful labors.

This was the type of a sensitive soul with ingrained feelings of a future harmony and unity.

Now for one more touching type of a collector.

A very poor officer in a line regiment, stationed in a distant provincial town, reaches out to art with all his soul. Depriving himself of many things Colonel Kratchkovsky, always pleasant in manner, always active, burning with enthusiasm, seeks to gather a collection of specimens of Russian painting. Of course he is unable to collect large pictures so he collects small pictures, sketches, studies, drawings. But his collection becomes a very considerable one in its essential value. He looks for the best painters; he understands that often the sketch is more valuable than the picture itself. He seeks to bring out the character of the artist in its most typical features. This is not a buyer of cheap pictures; this is a true collector. He himself is often in need of ten rubles (five dollars) and for him it is a matter of the greatest consequence whether he has to pay ten rubles more or less for a picture. He asks the painter to let him have the picture and persistently persuades him to lower the price. His words produced their effects and the sketches were given to him; he would rejoice with the bright joy of a child, and would write enthusiastic letters about his new treasure. How he loved art, and with what lofty meaning he surrounded the conception of true creative work.

In his will he bequeathed his entire collection to the public. More than that, he commanded that all his modest property, all that he had in his daily life, be sold and the proceeds applied to the purchase of more works of art which were to be added to his collection.

This is the type of an outwardly unnoticed but deeply important worker for the culture of the future. His example drew the attention of many, and if you could see his letters written from the battlefield! He was a pure soul. Colonel Kratchkovsky left us during the last war.

I might show you many more characters, full of noble seeking in different areas of art, but even these four types show the level of those cultural aspirations which are so necessary for humanity. Thus do things happen, not in dreams, but in real life—sincerely and actively, and such pure labors are accompanied by a smile of joy. How close are the seekings of art to the attainment of the spirit.

It is time to understand, note and to apply these wondrous channels to life.

And when art has entered actively, irresistibly and simply into all spiritual development of public life, then it will be brought also into all of modern life.

And it is through these channels that the true paths of blessing will draw near to every human heart.

Plato ordained in his treatises on statesmanship:

“It is difficult to imagine a better method of education than the one that has been discovered and verified by the experience of centuries; it can be expressed in two propositions: gymnastics for the body and music for the soul. In view of this, one must consider education in music as the most important; thanks to it, Rhythm and Harmony are deeply enrooted into the soul, dominate it, fill it with beauty and transform man into a beautiful thinker. . . . He will partake of the Beautiful and rejoice in it, gladly realize it, become saturated with it and will arrange his life in conformity with it.”

Of course the word music, in this case, should not be understood as routine musical education as it is understood now in its narrow sense. In Athens, as service to all Muses, music had a far deeper and broader meaning than it does today. This conception embraced not only the harmony of sound, but the whole realm of poetry, the whole domain of elevated perceptions, of exquisite forms, and of creation in general, in its best sense. The great service to the Muses was a real education of taste, which in everything cognizes the great Beautiful. And we shall have to return to this vital Beauty, unless Ideas of elevated constructiveness are to be completely rejected by Humanity.

Hippias Maior (beauty) of the dialogue of Plato is not a vague abstraction, but verily the most vital noble concept. Beauty exists in itself! It is sensed and realized. In this realization is contained an inspiring, encouraging call to the study and implanting of all the covenants of the beautiful. “The philosophical morale” of Plato is animated by the sense of the beautiful. Did Plato himself, who was sold into slavery because of the hatred of the tyrant Dionysius, not prove, later on, by his own example the vitality of the beautiful path when he was re-established and living in the gardens of the Academy,? Of course Plato’s gymnastics were not the coarse football or anti-cultural breaking of noses of modern prize-fights. The gymnastics of Plato were the same gates to the Beautiful, the discipline of Harmony and uplifting of the body into the spiritual spheres.

Not once have we spoken about the introduction in school of a Chair of Living Ethics, a course in the Art of Thinking. Without the education for the general realization of the Beautiful, these two courses will again remain a dead letter. Again in the course of only a few years, the lofty and vital principles of ethics will turn into a dead dogma if they will not be imbued with the Beautiful.

Many vital concepts of antiquity have become belittled and vulgar in our household, instead of their deserved expansion. Thus the wide and lofty service to the Muses has turned into a narrow conception of playing one instrument. When you hear nowadays the word music, you imagine first of all a lesson of music often with conventional limitations. When you hear the word Museum one understands it as a storeroom of all kinds of art objects. As with every store-house, this conception creates a certain flavor of deadliness. Such limited conceptions of the word Museum, as a storage place, so deeply entered our understanding, that when one pronounces this concept in its original meaning—Muzeon—then no one understands what is really meant. Yet every Hellene of even average education would at once know that Muzeon means first of all the home of Muses.

Foremost all Muzeon is the abode of all aspects of the Beautiful; not at all in the sense of only storing different kinds of art creations, but in the sense of the most vital and creative application of them in life. Thus nowadays one often hears that people express surprise when a Museum, as such, occupies itself with all spheres of art, with the education of good taste and with the spreading of the feeling for the Beautiful.

In this regard we recall the Covenants of Plato. So likewise we might have recalled Pythagoras with his “Laws about the Beautiful,” with his steadfast foundations of resplendent universal affirmations. The ancient Hellenes reached such a level of sensitivity that they proclaimed their Pantheon as an Altar to the Unknown God. In this ascent of the Spirit, they approach the inexpressible finesse of the understanding of the ancient Hindus who, on pronouncing “Neti, Neti”, did not thereby express something negative, but quite the opposite. In saying “Not That, Not That” they were pointing out the indescribable grandeur of an Unutterable Concept. It is significant that such great conceptions were not abstract, as if living only in the mind and reason; no, they dwelled in the very heart, as something living, life bringing, inalienable and indestructible, as defined so beautifully in the Bhagvad Gita. In the heart that sacred fire was aflame which was at the base of all flaming commandments also of the hermits of Mt. Sinai. The same sacred fire moulded the precious images of St. Theresa, St. Francis, St. Sergius and all Fathers of the “Love of the Good,” who knew so much and were understood so little.

We speak of the education of good taste as of a matter of truly basic world significance of every country. When we speak about vital ethics which should become the favorite school hour of every child, we appeal to the contemporary heart, pleading to it for expansion if even only to the extent of ancient ordainments.

Can one consider as natural the fact that the conception so glorified already in the time of Pythagoras and Plato, has become so limited now and has lost its actual meaning after all the ages of so-called progress? Pythagoras already, in the fifth century B.C., symbolized in himself the whole harmonious “Pythagorean Life.” It was Pythagoras who affirmed music and astronomy as sisters sciences. Pythagoras who was called a charlatan by bigots, must be horrified to see how, instead of a harmonious development, our contemporary life has been broken up and mutilated, and that we do not even understand the meaning of the beautiful hymn to the sun—to Light.

Today very strange formulas sometimes appear in the press. For instance, the flourishing of the intellect is the sign of degeneration. A very strange formula, if only the author does not attribute some special narrow meaning to the word intellect. Of course if the word intellect is only taken as being the expression of the conventional, withered mind, then to some extent, this formula may have its foundation. But it is dangerous in case the author does understand intellect as intelligence, which first of all should be connected to the education of good taste as the most vital principle of life.

Quite recently, before our eyes in the West, the new word—intelligentsia has been adopted. In the beginning, this newcomer was met rather suspiciously, but soon it was adopted in literature. It would be important to determine whether this expression symbolizes the intellect, or if, according to the ancient conceptions, it corresponds to the education of good taste.

If it is a symbol of refined and expanded consciousness then we have to greet this innovation, which perhaps will remind us once more of ancient beautiful principles.

In my letter “Synthesis”, the difference between the concepts of Culture and Civilization was discussed. Both these concepts are sufficiently separated even in standard dictionaries. Therefore let us not return to these two sequential concepts, even if someone would be content with the conception of civilization without dreaming about the higher concept of culture.

But having remembered the concept of the “intelligentsia” it will be permissible to ask, whether this concept belongs to Civilization, as an expression of intellect, or does it also embrace the highest step? To be exact, does it enter into the state of Culture, in which the heart and the spirit also act? Of course, if we would suppose that the word “intelligentsia” refers only to the stage of reason, then it would hardly be worthwhile to introduce it as a new usage. One may admit an innovation where it introduces something new, or at least sufficiently revitalizes the ancient principles within the frame of the present day.

Of course everyone will agree that intelligentsia, this aristocracy of the Spirit, belongs to Culture and only in this connection one could greet this new literary expression.

In this case the education of good taste belongs, of course, first of all to the intelligentsia, and not only does it belong, but it becomes its duty. Not fulfilling this duty, intelligentsia has no right to its existence and condemns itself to savagery.

The education of taste cannot be an abstraction. First of all, this is a vital achievement in all the domains of life, for otherwise where can the boundary of service to the muses as practiced by the ancient Hellenes be set? If the ancients understood this service in its entire scope and the application to life of these beautiful principles, should we not feel humiliated to clip the luminous wings of the fiery radiant angels through prejudice and bigotry!

When we suggest ethics as a subject for the schools, a subject most interesting, vast, full of creative principles, we thus offer the reformation of taste, as a fortification against ugliness.

Andromeda said, “I brought thee Fire.” And the ancient Hellenes, following Euripides, understood what Fire it was, and why it was so precious. But we in the majority of cases utilize these inspiring words of guidance like a phosphorous match. We think of the high concept of phosphorous, the carrier of Light, only as a match by which we ignite our cold hearth in order to cook our daily gruel. And where is tomorrow, this luminous, wonderful Tomorrow?

We have forgotten about it. We have forgotten it because we have lost our quests. We have lost our refined tastes which propel us toward improvement, aspiration and consciousness. Aspirations have become for us passing dreams; but the one who does not know how to aspire, does not belong to the future life, does not belong to the human kinship of a higher image.

Even the simple truth that the first distinction between man and beast is the former’s capacity to dream of the future has already become trite. But the truism itself has not become the commonly-accepted truth as it should be, but only a synonym for truth about which one need not think. Nevertheless, in spite of everything, in times of even the greatest difficulties, let us not postpone or delay anything concerning the education of taste. Let us not delay our thoughts on the subject of Light-bearing Ethics. Let us not forget about the art of thinking and let us remember about the treasure of the heart.

“A certain hermit left his retreat and came with the message, saying to everyone: ‘Thou hast a heart.’ When he was asked why he does not speak about mercy, patience, devotion, love and all other benevolent foundations of life, he replied ‘If they only do not forget the heart, the rest will adjust itself! Verily can we appeal for love, if it has no place to reside? And where could patience dwell, when its abode is closed? Thus, in order not to be tormented by goodness unapplied, one must create a garden for it, which will flourish in the midst of the realization of the heart.. Let us stand firmly on the foundation of the heart and let us understand that without the heart we are as a perishable shell.” Thus the wise ones ordained. Thus ordains Agni Yoga. Thus let us accept and apply.

Without the untiring realization of the Beautiful, without incessant refinement of the heart and consciousness, we would make the laws of earthly existence cruel and deadly in their hatred against humanity. In other words, we would, by killing the Beautiful, help contribute to the most shameful, debased destruction.

The Romans said: Sub pretextu juris summum jus saepe summa injuria; suaviter in modo fortifer in re. (Under pretext of justice a strict application of law is often the gravest injury. Be gentle in manner thou, resolute in execution).

Let us be broad and resolute in the realization of the Beautiful!

Vivekananda said: “The artist is a witness of the Beautiful.”

Rabindranath Tagore finishes his book What is Art? with such words: “In Art the person in us is sending its answer to the Supreme Person who reveals Himself to us in a world of endless beauty across the lightless world of facts.”

There is no other way, O friends scattered! May my call penetrate to you. Let us join ourselves by the invisible threads of the Beautiful. I turn to you, I call to you: In the name of Beauty and Wisdom, let us combine for struggle and work. During days of Armageddon let us ponder about Eternal Values, which are the cornerstones of Evolution.

In the name of Culture I send you from the Himalayas my heartiest greetings!

“The artist is the priest of the Beautiful. It is he who rescues the truth from its ugly defilement and allows us to drink of the perennial fount of joy amidst the fret and stress of life.”

“The beautiful is scattered throughout the universe like the auriferous sands!”

So writes Bhabes Chandra Chaudhuri in his article “The Artist and the Beauty in Art.”

It is joy to read such an appreciative article in which the artist himself affirms the significance of Beauty. There was a time when it was considered, for some reason, that an artist should not be a writer. Sometimes such artificial preconceptions went so far as to say that a talented composer, according to the judgment of his impresario, should not be permitted to appear in public as a conductor, as it was believed that public opinion would thereby be confused. One can imagine how Leonardo da Vinci, Vasari or Cellini would laugh at such an absurd way of obstructing creative thought.

It seems that in the history of art there are many convincing examples of how people who devoted themselves to Beauty expressed it in a multitude of ways, choosing that which at the moment appeared to them the best way to do so. How beautifully they combined painting with architecture, or with sculpture, not to speak of mosaics and various graphic arts.

As priests they served Beauty, finding the most persuasive expressions for their beneficent influence on the general masses, and for refining the consciousness of the people.

In India today we notice a renaissance of art. There appear glorious hosts of artists. State Galleries are being opened, and frescoes again adorn public buildings. The best artists are heading Art Schools, and art is sure to be found in many monthly journals and magazines. The artificial barriers between so-called “great art” and “applied art” are breaking down. Verily Beauty is great in all its variety. It is a pleasure to find a page on art and many reproductions of art both modern and ancient in many monthly journals and magazines.

Someone may smile and think: “This sounds very encouraging, but what of the difficult life artists lead?” Of course their lives are not easy, nor is any heroic achievement. No one will think that the lives of Rembrandt or Rubens were easy. It is only in recent times that their names have become great collective concepts above any doubts. But we know that the beautiful masterpieces of Rembrandt which he was commissioned to paint were rejected by the local authorities and municipalities. We also know that Leonardo in Florence and Michel Angelo in Rome experienced great hardships. Time adorns all sufferings with epic beatitude and calm. Yet how many tragedies remain hidden behind the gorgeous brocaded curtains of Time.

We all know the martyrdom of scientists like Copernicus, Galileo, Paracelsus, Lavoisier and innumerable other sufferers for truth. There exist entire books dedicated to these martyrs of Science. And next to them there should also exist volumes entitled “Martyrs of Art and Culture.” However, once we know that artists are priests of the Beautiful, we also know that the attainment of all other attributes is inevitable.

Much has been written about vandalism. We introduced the Banner of Peace as a Red Cross of Culture to protect real treasures of humanity. And now let me mention another hidden but cruel vandalism, which quietly exists in the life of many nations.

When studying old masters, we often come across the fact that many very good paintings were for some reason overpainted with entirely different subjects by inferior artists. It is obvious that the old painting had become old-fashioned and the artist simply used the wood as material for his modern and more fashionable expressions. One should not think that only paintings of secondary importance were subjected to such barbaric manipulations. On the contrary, amongst the recorded cases we find some very important ones which today occupy a place of honor in the history of art.

I remember how once in Italy while studying a beautiful painting “Virgo Inter Virgines,” we were surprised at its exceptionally good condition. When expressing our amazement at this, we received the following unusual but characteristic explanation: “Apparently at the beginning of the 17th Century this beautiful painting was already considered old-fashioned and therefore, despite the religious subject, it was covered by another religious subject, ‘Ecce Homo,’ and had remained all the time in a certain monastery. This second painting was by far inferior to the original masterpiece. It was noticed comparatively recently that the outlines of a different composition were becoming vaguely discernible through the second painting, and the person who had purchased this inexpensive painting from the monastery decided to remove the upper layer, thus revealing a beautiful masterpiece.” Now this painting adorns the Art Institute in Chicago.

I have also personally seen an old replica of the well-known painting by Corregio which is in the National Gallery in London. On this replica I could clearly see the outlines of an ancient portrait, and indeed the panel on which it was painted proved to be far older than the replica. Once we had occasion to witness how, from beneath paintings of the 17th and 18th centuries beautiful originals appeared in good condition by Lambert, Lombard, Rogier van der Weyden, Adrien Bloemaert and similar renowned artists. In the Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston we find a most instructive story about the portrait of Sir William Butts, by Hans Holbein the Younger. Let us quote a few lines from this article:

“On November 17, 1935, the Museum purchased the striking portrait by Hans Holbein the Younger.... Connoisseurs, seeing the portrait, refused to believe that Holbein could have done it, and with good reason. As it appeared for about three and a half centuries it was certainly not Holbein. In very recent times, however, a young friend of the Butts family which had retained possession of the painting from the time it was done until it passed to the Museum, H. M. Jonas, remarked that the hands seemed to be painted in a manner somewhat different from the rest of the portrait and suggested an earlier style. He was permitted to have an X-ray made and the result was the discovery of a portrait underneath. The X-ray showed a different outline to the cap, a full beard, a different chain and a suit puffed with white silk. It also revealed the existence of an inscription on the background. Next came the difficulty of the restoration. The first restoration was undertaken by Nico Jungman. It was an extremely difficult task, since the overpainting was of very nearly the same period as the painting underneath. It is obvious that the sitter caused his portrait to be repainted later in life. We cannot be sure when this was done, though it was probably in 1563 when Queen Elizabeth came to Thornage and was elaborately feted. It is likely that then, Sir William, an old man holding high offices, demanded that he be shown with different garments and ornaments added, and therefore had himself repainted, presented in regalia and brought up-to-date, but unfortunately by a very inferior artist.”

This interesting story has two corollaries. First, we must pay tribute to the administration of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and to the restorer, who have completed this most difficult restoration so successfully, and thus have revealed to the world the original masterpiece of a great artist without any later inferior additions and overpainting. Secondly, this instructive historical episode shows to us once more that vandalism is committed not only by the hands of an infuriated mob but also tacitly in highly distinguished dwellings for the sake of vanity and prejudice.

Beauty cannot be guarded by orders and laws alone. Only when human consciousness realizes the inestimable value of beauty—creating, ennobling and refining —only then will the real treasures of humanity be safe. And one should not think that vandalisms, obvious or tacit, belong only to past ages, to some fabulous invaders and conquerors. We see vandalism of many kinds taking place even today. Therefore the endeavour to protect and save beauty is not an abstract nebulous move, but is imperative, real and undeferrable.

Verily education in art and beauty is a necessity with all its duties and obligations. We always rejoice when we see that thoughts are being transmuted into action. It is for this reason that the opening of new schools, the inauguration of an International Academy of the Arts, is always to be greatly welcomed.

Twenty years ago we wrote upon the shields of the Master Institute of United Arts and of the International Art Centre the following mottoes:

Art will unify all humanity. Art is one—indivisible. Art has its many branches, yet all are one. Art is the manifestation of the coming synthesis. Art is for all. Everyone will enjoy true art. The gates of the “sacred source” must be wide open for everybody, and the light of art will influence numerous hearts with a new love. At first this feeling will be unconscious, but afterwards it will purify human consciousness. How many young hearts are searching for something real and beautiful! So, give it to them. Bring art to the people—where it belongs. We should have not only museums, theaters, universities, public libraries, railway stations and hospitals, but even prisons decorated and beautified. Then we shall have no more prisons.

Humanity is facing the coming events of cosmic greatness. Humanity already realizes that no occurrences are accidental. The time for the construction of future culture is at hand. Before our eyes re-evaluation of values is being witnessed. Amidst ruins of valueless banknotes, mankind has found the real value of the world’s significance. The values of great art are victoriously traversing all storms of earthly commotions. Even the “earthly” people already understand the vital importance of beauty that is alive. And when we proclaim love, beauty and action, we know verily that we pronounce the formula, of the International language. And this formula which belongs to the museum and stage must enter daily life. The sign of beauty will open all sacred gates. Beneath the sign of beauty we walk joyfully. With beauty we conquer. Through beauty we pray. In beauty we are united. And now we affirm these words—not on the snowy heights, but amidst the turmoil of the city. And realizing the path of true reality, we greet the future with a happy smile.

Twenty years have elapsed and we see that all the requirements of Beauty have become still more urgent. Everything that has been done in this direction still remains as if it were on isolated islands. Beauty does not tolerate conventional limitations and boundaries. The treasures of beauty belong to the world. Hence the care for art and knowledge is also a universal duty on a planetary scale.

Culture—the veneration of Light—rests on the cornerstones of Beauty and Knowledge. And if there was a beautiful necessity to inaugurate the Red Cross of Culture and a universal Banner reminding men of the treasures of Culture—it means that this beautiful necessity also was undeferrable. Culture, Beauty and Science are violated not only in times of war, but also in times of so-called peace. This truth again refers to the whole world.

If anyone should possess a receptacle containing a wonderful panacea, how carefully would he guard such a treasure. But beauty is that same miracle-working panacea and as such requires a vigilant devotion. Now cures are affected in hospitals by sound and color—thus Beauty, the perfect panacea, enters in a new garment. People worry about their health. May this consideration at least teach them to venerate and guard the panacea of Beauty. Half a century ago our great Dostoyevsky proclaimed: “Beauty will save the world.”

Amidst the touching definitions of art I recollect two legends, one from Chinese Turkestan, the other from Tibet.

An artist wanted some money for his painting and when he came to the moneylender, the man was absent and only a boy was there. This boy gave the artist a very large sum for the painting. When the moneylender came back, he said: “For these fruits and vegetables you gave such a great sum!” and he discharged the boy. Time passed and the artist returned and asked for the painting. When he saw it he was horrified, saying: “That is not my painting. Where are the butterflies? Go find the boy that he may help us find my painting. This painting you show me has only cabbages.” The boy came and said: “Now it is winter, and the butterflies come only in the summer time. Put the painting near the fire, and we shall see the butterflies return.” And so it was; the paint was put on the canvas so skilfully that during the cold weather the colors receded, but in the warmth they returned. Thus do the people of Kuchar speak beautifully about the perfection of art.

And the other from Tibet: Why do the giant trumpets in the Buddhist temples have such a resonant tone? The ruler of Tibet decided to summon from India, from the place where the Blessed One dwelled, a great Teacher, in order to purify the fundamentals of teaching. How to meet the esteemed guest?

Gold and precious gems would not be adequate to meet a spiritual Teacher. Then the High Lama of Tibet, having had a vision, gave the design for a new giant trumpet so that the guest could be received with unprecedented majestic sound; and the meeting was a wonderful one—not with the wealth of gold but with the grandeur of the beautiful sound.

The master could be greeted only with something beautiful: The sense of the beautiful must be that life-giving seed—that real panacea, which makes the deserts, both physical and spiritual, flourish.

And from where else can a sense of Goodwill and Unity come if not through the Blessed realization of the Beautiful!

One recalls an incident: Two visitors are In the office of a certain president. The walls of the old room are decorated with massive oak bookcases. Through the glass panels temptingly glow the backs with their rich bindings. Although the bindings are not old, they are heavily gold-leaved. Apparently here is a lover of books. How splendid that at the head of this undertaking there is a collector who has not spared money on his alluring bindings.

One of the visitors yields to the temptation of turning the leaves and holding this treasure of the spirit in his hands. The bookcase is apparently unlocked and raising his hand the booklover attempts to take one of the volumes. But, oh, horror! the entire shelf falls on his head, revealing that these are false bindings without any sign of a book. His most sensitive wish violated, the booklover with trembling hands, replaces this unworthy imitation upon its shelf: “Let us get away from here as soon as possible. Can one expect anything decent from such a clown?!” The other visitor smiles. “Here one is punished for loving books: Because it is a happiness not only to read a good book, but even to hold it in one’s hands.”

How many such false libraries are spread all over the world? And whom do their owners presume to cheat—their own friends or themselves? In this falsification lies hidden an unusually subtle disdain of knowledge and a refined insult towards the book as the witness of human achievement. And not only are the contents of the book being violated, but in such falsifications, objective as well as in words, the very significance of the creation of the spirit is being assaulted.

“Tell me who are your enemies and I will tell you who you are,” said the ancients. One may say: “Show me your bookcase and I will tell you who you are.”

One of the most exhausting tasks is the search for a new apartment. But through this involuntary intrusion into numerous dwellings, you undoubtedly discover observations about the facts of life. You pass through numerous apartments of approximate wealth which are not yet filled with furniture. But where is the bookcase? Where is the writing desk? Why are the rooms sometimes overcrowded with such strange ugly objects, yet these two friends of existence—a writing desk and a bookcase are lacking? Is there a place to put them? It appears upon examination that a small desk could still be placed somewhere but the walls are all so covered, that there is no place for a bookcase.

Every librarian is a friend of the artist and scientist. The librarian is the first messenger of Beauty and Knowledge. It is he who opens the gates and from the dead shelves extracts the hidden word to enlighten the searching mind. Not one catalogue may replace a librarian. A loving word and experienced hand may produce the miracle of enlightenment. We affirm that beauty and knowledge are the basis of the entire culture, and these are changing the whole history of humanity. This is not a dream. We can prove it through all of history. The immutable facts tell us how, from primitive ages, all progress, all happiness, all enlightenment of humanity was led by Beauty and Knowledge.

It is not strange to speak these words at a time when millions of books are printed; every year a torrent of printed pages forms new snowy mountains. In this labyrinth of paper glaciers, true snow blindness can strike the inexperienced traveler. But the librarian, as a true honor guard of knowledge, is vigilant. Only he knows how to steer the boat through the waves of this ocean of past and future.

The library exists not only to spread knowledge. Each library is an introduction to bringing knowledge into the home. Is it possible to imagine a home and a household without books? Again, if you will take the most ancient images of the home and household, the finest examples revealed are objects and books. And you can see that these old books, in their beautiful bindings, were held as a true treasure. And not because the library did not exist. Librarians existed throughout the ages. But the human spirit feels that knowledge can be acquired, not only in public places, but also in the calm of the home. We even carry the most sacred books and images with us. They are our unchangeable friends and guides. We know perfectly that it is not worthwhile to read a book once. As magical signs, the truth and beauty of the book is absorbed gradually. And we do not know either the day or the hour when we need the gospel of knowledge. So, the library is the first step of enlightenment. But the true upliftment of knowledge comes in the hour of silence, in solitude when we can concentrate all our intelligence towards the true meaning of scriptures.

Books are true friends of humanity and each human being is entitled to have these noble possessions. In the East, in the wise East, a book is the most precious gift. And he who gives the gift of a book is regarded as a noble man. During five years of travel in Asia we have seen innumerable libraries in each monastery, in every temple, in every ruined Chinese watch tower. There was a library with collections of the most remarkable books—and collections of famous biographies, dictionaries, history and the sciences.

When you see a lonely traveler in the mountains, you may be sure that a book is in his knapsack. You may deprive him of everything, he will be resigned to it, but he will fight for his real treasure, the book.

So, let us remember that books are real treasures and let us collect and cherish them as the noble crest of our home.

Once in Karelia I sat on the shores of Lake Ladoga with a farm lad. A middle-aged man passed us by and my small companion stood up and with great reverence took off his cap. I asked him after, “Who was this man?” And with special seriousness, the boy answered, “He is a teacher.” I again asked, “Is he your teacher?” “No,” answered the boy, “he is the teacher from the neighboring school.” “Then you know him personally?” I persisted. “No,” he answered, with astonishment. . . . “Then why did you respect him with such reverence?” Still more seriously my little companion answered, “Because he is a teacher.”

An almost similar incident happened to me on the banks of the Rhine. Again with joyous amazement I saw how a young man greeted a school teacher. I recall the most uplifting memories of my teacher, Professor Kuindzhi, the famous Russian artist. His life story could fill the most inspiring pages of a biography for the young generation. He was a simple shepherd boy in the Crimea. Only by incessant, ardent effort towards art was he able to conquer all obstacles and finally become, not only a highly-esteemed artist and a man of great means, but also a real Guru for his pupils in the high Hindu conception.

Three times he tried to enter the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts and three times he was refused. The third time, twenty-nine competitors were admitted and not one of them left his name in the history of art. But only one, Kuindzhi, was refused. The Council of the Academy was not made up of Gurus, and certainly was short-sighted. But the young man was persistent and instead of uselessly trying, he painted a landscape and presented it to the Academy for Exhibition. He received two honors without passing the examination. From early morning he worked, but at noon he climbed up to the terraced roof of his house in Petrograd, where, with the shot marking each midday, thousands of birds completely surrounded him. He fed them, speaking to them, studying them as a loving father. Sometimes, very rarely, he invited us, his disciples, to his famous roof, and we heard remarkable stories about the personalities of the birds, about their individual habits and the ways to approach them. At this moment, this short stockily-built man with his leonine head, became as gentle as Saint Francis. Once I saw him very downcast during the entire day. One of his beloved butterflies had broken its wing and he had invented some very skilful means to mend it, but this invention was too heavy and he had been unsuccessful in this noble effort.

But with his pupils and artists, he knew how to be firm. Very often he repeated: “If you are an artist, even in prison, you shall become one.” Once a man came to his studio with some very fine sketches and studies. Kuindzhi praised them. But the man said: “Well I am unfortunate because I cannot afford to continue painting.” “Why?” Kuindzhi asked compassionately, and the man said that he had a family to support and was employed from ten to six. Then Kuindzhi asked him piercingly: “And from four to ten in the morning, what do you do?” “When?” asked the man. Kuindzhi explained, “Certainly in the morning.” “In the morning I sleep,” answered the man. Kuindzhi raised his voice and said. “Well, you shall sleep away your entire life. Don’t you know that four to nine is the best creative time? And it is not necessary to work on your art more than five hours a day.” Then Kuindzhi added; “When I worked as a retoucher in a photographic studio, I also had my job from ten to six. But from four to nine I had quite enough time to become an artist.”

Sometimes, when the pupil dreamed about some special conditions for his work, Kuindzhi laughed. “If you are so delicate that you have to be put in a glass case, then better perish as soon as possible, because our life does not need such an exotic plant.” But when he saw that his disciple conquered circumstances and went victoriously through the ocean of earthstorms, his eyes sparkled and in full voice, he shouted. “Neither sun nor frost can destroy you. This is the way. If you have something to say you will be able to manifest your message in spite of all the conditions in the world.”

I recall how once he came to my studio on the sixth floor, which at that time was without an elevator, and severely criticized my painting. Thus, he left practically nothing of my original conception, and in much uproar he went away. But in less than half an hour, I heard his heavy steps again, and he knocked on the door. Again he had climbed up the long steps in his heavy fur coat, and said: “Well, I hope you shall not take everything I said seriously. Everyone can have his point of view. I felt badly when I realized that perhaps you took all of our discussion too seriously. Everything can be approached in different ways, and really, truth is infinite.”

And sometimes, in the greatest secrecy, he entrusted one of his disciples to bring some money anonymously from him to some of the poorest students. And he entrusted this only when he was completely confident that this secret would not be revealed. It happened once that in the academy, revolt against the Vice President Count Tolstoy arose, and as no one could calm the anger of the students, the situation became very serious. Then finally Kuindzhi arrived at the general meeting, and everyone became silent. He said: “Well I am no judge. I do not know if your cause is just or not, but I personally ask you to begin your work because you have come here to be artists.” The meeting was ended at once, and everyone returned to the classrooms, because Kuindzhi himself had asked. Such was the authority of the Guru.

I do not know from where this conception of real Guruship arose in the refined Eastern understanding. Certainly he expressed it sincerely, without any superficial intention. This was his style and in the sincerity of this style, he conquered not only as an artist but also as a powerful vital type who gave his disciples the same broad inflexible power to reach their goal.

Long afterwards in India, I saw such figures of Gurus and I have seen the faithful disciples who without any servile obeisance, but rather with great enthusiasm of spirit, venerated their Gurus with that full sensitivity of thought which is so characteristic of India.

Our responsibility before the Beautiful is great! If we feel it, we can demand the same responsibility to this highest principle from our pupils. If we know that this is a necessity, as during an ocean storm, we can require of our companions the same attention to the ardent demand of the moment.

We are introducing, by all means, art into all manifestations of life. We are striving to show the quality of creative labor, but this quality can be recognized only when we know what ecstasy is experienced before the beautiful; this ecstasy is not that of a transfixed image, but is motion, an all-vibrating Nirvana. This is not only the falsely-conceived Nirvana of immobility, but the Nirvana of the noblest and most intensive activity. In all ancient teachings, we have heard about the nobility of action. How can these actions be noble, if they are not beautiful? You are the teachers of art; you are the emissaries of beauty; you know the responsibility before the coming generation and in this is manifested your joy and your invincible power. Your actions are the noble actions.

And to you, my young unseen friends, we are sending out our call. We know how difficult it is for you to begin the struggle for light and achievement. But the obstacles are only new possibilities to create beneficent energy. Without battle, there is no victory. And how can you avoid the venomous arrows of the dark enemy? By approaching your enemy so closely that he shall lack space even to send an arrow. And after all, nothing enlightened may be achieved without travail. So blessed be labor. And blessed be you, young friends, who are walking in victory! The Gurus of the past and future are with you.

Gurus, to you my invocation and my reverence!

Our Times are verily difficult, because of all the commotions, all the lack of understanding and all attacks of darkness against Light. Quite recently there were pictures in magazines showing the auto-da-fé of precious books in the streets. It is hard to realize that this could have taken place in the present age, after millions of years of the existence of our planet. But perhaps this terrible tension is the impulse to direct humanity through all storms and over all abysses to peaceful construction and mutual respect. What an epoch-making day might be before us when over all countries, all centers of spirit, beauty and knowledge, the One Banner of Culture could be unfurled! This sign would call everyone to revere the treasures of human genius, to respect culture and to have a new recognition of labor as the only measure of true values. From childhood, people will witness that there exists not only a flag of human health but there also is a sign of peace and culture for the health of the spirit. This sign, unfurled over all treasures of human genius will say: “Here the treasure of all mankind are guarded; here above all petty divisions, above illusory frontiers of enmity and hatred, the fiery stronghold of love, labor and all-moving creation is towering.”

Real Peace, Real Unity is desired by the human heart. It strives to labor creatively and actively for its labor is a source of joy. It wants to love and expand in the realization of Sublime Beauty. In the highest perception of Beauty and Knowledge all conventional divisions disappear. The heart speaks its own language; it wants to rejoice what is common to all, what uplifts all, and what leads to the radiant Future. All symbols and tablets of humanity contain one hieroglyph, the sacred prayer—Peace and Unity.

It is truly beautiful, if amidst the turmoil of life, in the waves of unsolved social problems, we still may hold up before us the eternal flambeau torches of peace in all ages. It is beautiful, through the inexhaustible well of love and tolerance, to understand the great movements which connected the highest knowledge to the highest aspirations. Thus, by studying and admiring we are becoming real cooperators with evolution, and out of the brilliant rays of the Supreme Light may emerge true knowledge. This refined knowledge is based on real comprehension and tolerance. From this source comes the great understanding, emerges the Supremely Beautiful, the enlightenment and enthusiasm for Unity. Contemporary life is changing rapidly, the signs of a new evolution are knocking on all doors. In real, unconventional science we feel the splendid responsibility before the coming generations. We gradually understand the harm of everything negative. We begin to value enlightened positiveness and constructiveness, and in this measure, in merciful tolerance, we can prepare a vital happiness for our next generation, turning vague abstractions into beneficent realities.

On the scrolls of command it has been inscribed that a spiritual garden is in daily need of the same watering as a garden of flowers. If we still consider the physical flowers the true adornment of our life, then how much more must we remember and prescribe to the creative values of the spirit the leading place in the life which surrounds us? Let us then, with untiring eternal vigilance, benevolently mark the manifestations of the workers of culture; and let us strive in every possible way to ease this difficult path of heroic achievement.

Let us also mark and find a place in our lives for the great ones, remembering that their name no longer is personal with all the attributes of the limited ego, but has become the property of pan-human culture, and must be safeguarded and firmly cared for in the most benevolent conditions.

We shall thus continue their self-sacrificing labor and we shall cultivate their creative sowing which, as we see, is so often covered with the dirt of noncomprehension and overgrown with the weeds of ignorance.

As a caring gardener, the true culture-bearer will not forcefully crush those flowers which entered life not from the main road if they belonged to the same precious kinds which he safeguards. The manifestations of culture are just as manifold as are the manifestations of the endless varieties of life itself. They ennoble Be-ness. They are the true branches of the one sacred Tree, whose roots sustain the Universe.

If you shall be asked, of what kind of country and of what kind of future constitution you dream, you can answer with full dignity: The country of Great Culture shall be your noble motto. You shall know that in that country there will be peace, a country where knowledge and beauty will be revered.

Everything created by hostility is impracticable and perishable. The history of mankind gave us remarkable examples of how necessary just peaceful creativeness was for progress. The hand will tire from the sword but the creating hand sustained by the might of the Spirit is untiring and unconquerable. No sword can destroy the heritage of culture. The human mind may temporarily deviate from the primary courses, but at the predestined hour, it will have to return to them with the renewed powers of the spirit.

Culture and Peace make man verily invincible; realizing all spiritual conditions, he becomes tolerant and all-embracing. Each intolerance is but a sign of weakness. If we understand that every lie, every fallacy shall be exposed, it means that, first of all, a lie is stupid and impracticable. But what has he to hide who has consecrated himself to Peace and Culture? Helping what is near to him, he helps the general welfare which was appreciated in all ages. Striving for Peace, he becomes a pillar of a progressing State. Not slandering what is near to us, we increase productiveness. Not quarreling, we shall prove that we possess the knowledge of the foundations. Not wasting time in idleness, we shall prove that we are true co-workers in the plough-field of Culture. Finding joy in daily labor we show that the concept of Infinity is not alien to us. Not harming others, we do not harm ourselves, and in eternally giving we realize that in giving we receive. And this blessed receiving is not a hidden treasure of a miser. We understand how creative is affirmation and how destructive is negation. Amidst basic concept, those of Peace and Culture are the conceptions which even a complete ignoramus will not dare to attack. There where is culture, there is peace. There where is the right solution for the difficult social problems is achievement. Culture is the cumulation of highest Bliss, of highest Beauty, of highest Knowledge.

We are tired of destruction and negations. Positive creativeness is the fundamental quality of the human spirit. Let us welcome all those who, surmounting personal difficulties and casting aside petty selfishness, propel their spirits to the task of preserving culture, thus insuring a radiant future. We must not fear enthusiasm. Only the ignorant and the spiritually impotent would scoff at this noble feeling. Such scoffing is but the sign of inspiration for the true Legion of Honor. Nothing can impede us from dedicating ourselves to the service of Culture, so long as we believe in it and give it our most ardent thoughts.

Do not disparage! Only in harmony with evolution can we ascend! And nothing can extinguish the selfless and flaming wings of enthusiasm!

To the sacred ideals of nations in our days the watch-words: ‘Art and Knowledge,’ have been added with special imperativeness. It is just now that something must be said of the particular significance of these great conceptions both for the present time and for the future. I address these words to those whose eyes and ears are not yet filled with the rubbish of everyday life, to those whose hearts have not yet been stopped by the lever of the machine called ‘Mechanical civilization.’

Art and Knowledge! Beauty and Wisdom! It is not necessary to speak of the eternal and still renewed meaning of these concepts. Every child already instinctively understands the value of decoration and knowledge when but starting on the path of life. Only later, under the grimace of disfigured life this light of the spirit becomes darkened, for while in the kingdom of vulgarity it has no place and is unknown. Yes, the spirit of the age attains even to such monstrosity!

It is not the first time that I have knocked at these gates and I here again appeal to you.

Amongst horrors, in the midst of the struggles and collisions of the people, the questions of knowledge and of art are matters of primary importance. Do not be astonished. This is not an exaggeration, nor is it a platitude. It is an unequivocal affirmation, the only road to Peace.

The question of the relativity of human knowledge has always been much argued. But now, when the whole of mankind has felt, the horrors of war directly or indirectly, this question has become a vital one. People have not only become accustomed to think, but even to speak without shame about things of which they evidently have not the slightest knowledge. On every hand men repeat opinions which are altogether unfounded, and such judgments bring great harm into the world, an irreparable harm.

We must admit that during the last few years, European culture has been shaken to its very foundation. In the pursuit of things whose achievement has not yet been destined to mankind, the fundamental steps of ascent have been destroyed. Humanity has tried to lay hold onto treasures which it has not deserved and thus has rent the benevolent veil of the goddess of happiness.

Of course, what mankind has not yet attained it is destined to attain in due time, but how much man will have to suffer to atone for the destruction of the forbidden gates! With what labor and self-denial shall we have to build up the new foundations of culture!

The knowledge which is locked up in libraries or in the brains of the teachers again penetrates but little into contemporary life. Again it fails to give birth to active work.

Modern life is filled with the animal demands of the body. We come near to the line of the terrible magic circle, and the only way of conjuring its dark guardians and escaping from it is through the talisman of true Knowledge and Beauty.

The time when this will be a necessity is at hand.

Without any false shame, without the contortions of savages, let us confess that we have come very near to barbarism; confession is already a step towards progress.